Differentiable Drawing

Tyler Kvochick - 7 February 2019

What’s All This, Then?

Harvard Business Review and Autodesk recently published a white paper on the emerging practice of generative design. In it, they write:

Manufacturers of all sizes can use advanced generative design tools, which employ algorithms to transform a designer’s requirements into product geometry, optimizing the product design based on the conditions and constraints provided. The tools can provide a plethora of design options in the amount of time it would take engineers to set up a meeting to discuss just one.1

While this sounds promising, it is too vague to explain what is happening inside these “generative design tools” that makes them different in a meaningful way. Software companies continue this trend of making vague, non-technical promises that began with the incorporation of software into all industries around 40 years ago. Since then, professionals of all disciplines have gained software tools with the promise of new ways of working, but without an understanding of how the tools work.

We would like to explain how machine learning can be useful to design disciplines and to do that with more than superficial technical depth. If any given professional in the AEC industry comes away with an understanding of the abilities and limitations of machine learning, we will consider this article to be successful. Our goal is not to provide an education in contemporary machine learning techniques. Rather, we want to give examples of how machine learning is different from typical software development and what that can do for architects or designers. We will do so with enough references that someone can start researching the terms for themselves if they are interested to gain a deeper understanding of the technology.

Machine Reading

Suppose that we needed to turn a collection of as-built drawings into a BIM model. How would we go about doing this? Traditionally, someone would assemble the drawings into a 3D model and then reconstruct all of the building elements from the 2D information. But is there a way we can automate this process to free up this person to solve a more difficult design problem?

In order to do this task, either a person or a machine needs to be able to read drawings and decide to place certain categories of objects at their corresponding locations. Reading architectural drawings is a non-deterministic function. That is, there are many collections of pixels that could all correspond to the category “door,” for instance.

Having to program all of the rules that determine “doorness” (in plan) would require the explicit encoding of logic like so:

A door is a shape that has an arc next to a straight line that is perpendicular to a wall. Sometimes there are two sets of straight lines and arcs which could be the same size or different sizes. Sometimes those shapes aren’t there at all, and there is just a gap in the wall with a line or an arrow in between.

This encoding doesn’t take into account the nested concepts here (what’s a wall?) or the fact that we haven’t determined how to get from pixels in the drawing to the associated categories, or what happens when the image isn’t perfectly centered in the frame. And then, we need to find a way to solve all of these problems for every category of thing that could be encountered in architectural drawings, such as windows, furniture, technology devices, plants, etc. With all of this in mind, it seems as if this task is intractable and we should just resign ourselves to tedium until the end of time.

What machine learning leverages is the ability to program a machine to do these types of tasks in the same way that we would program a human: experience. A neural network, for instance, can be given thousands of examples of doors and learn to identify them without having to introduce any of the associated concepts in human language.

Deep Pixel Stacks

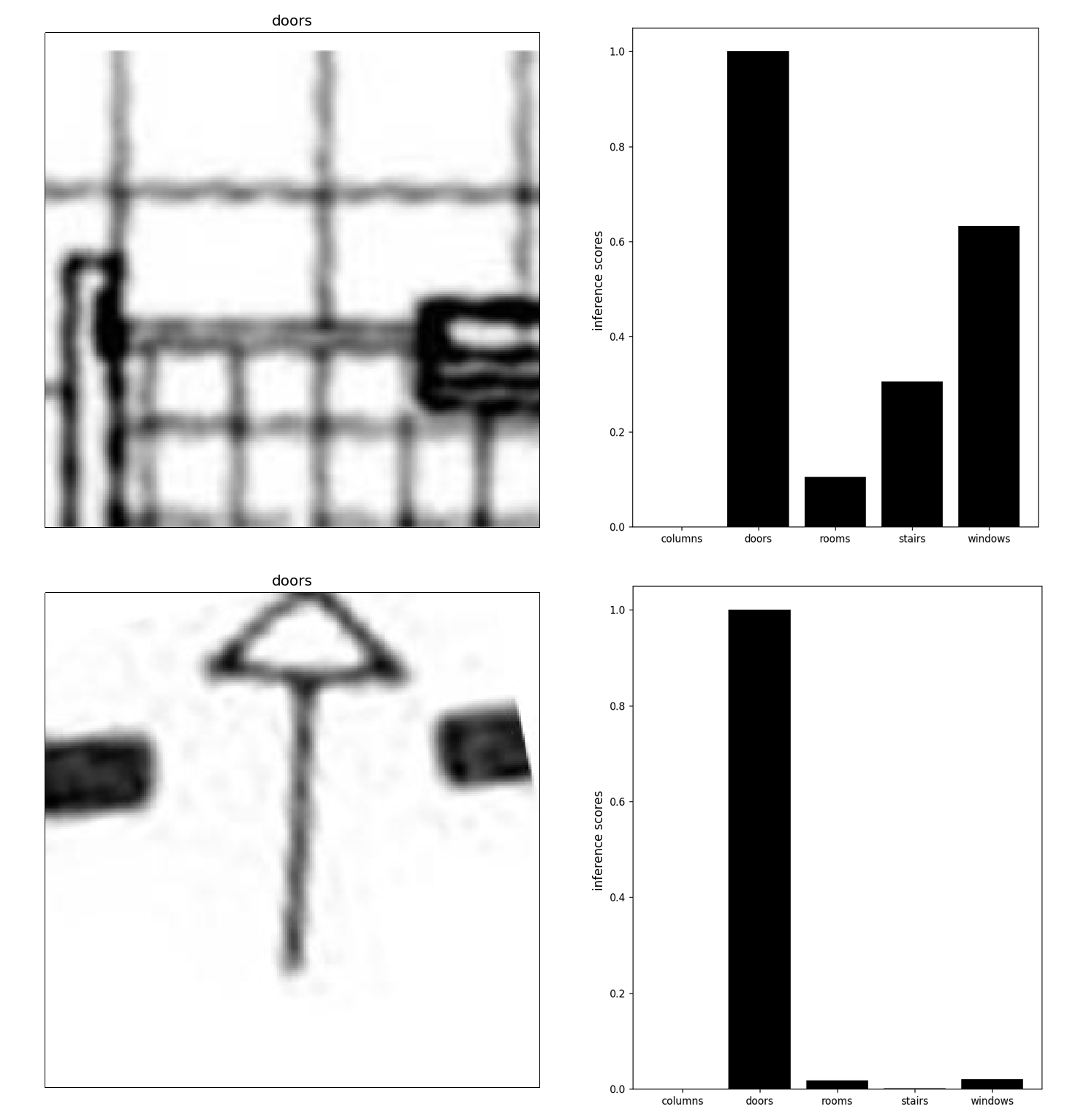

It turns out to be somewhat trivial to train a neural network to an accuracy of around ninety percent at identifying architectural elements. By making use of transfer learning — which takes a general purpose classification network and fine tunes the training for a particular purpose — it is possible to reuse the features that are useful for identifying many different classes of images and learn some new ones that are unique to a domain-specific task. In the image below, we can see that a neural network architecture called DenseNet2 is able to correctly identify a couple example images from a verification set of unseen door symbols. The images on the left are examples of plan drawings of doors that were withheld from the training set. The images on the right are a graph of the predicted scores over the output classes. Both are correctly identified with the maximum probability being assigned to the “door” class.

Thus, if we were to continue building our As-Built BIM Builder tool to free up our hypothetical employee, we could conceivably use this neural network to scan through plans and place doors at the locations where the network returns its strongest door scores. But how did we avoid the explicit programming of all the doorness rules? Neural networks function by using tensors to set up many possible code paths. A tensor is just a more general name for matrices or vectors or any collection of numbers that are organized into orthogonal axes. The shapes of the tensors determine the paths through the network and the values that they hold control how strongly the paths connect. During training, these paths are turned on or off (or somewhere in between) based on how well they help to assign one of the labels to the input.

If we take some subset of an architectural drawing that is encoded as an image, we can think of the neural network processing it to be a stack of thousands of very small images and some rules for combining them. In effect, they are a kind of deep pixel stack.

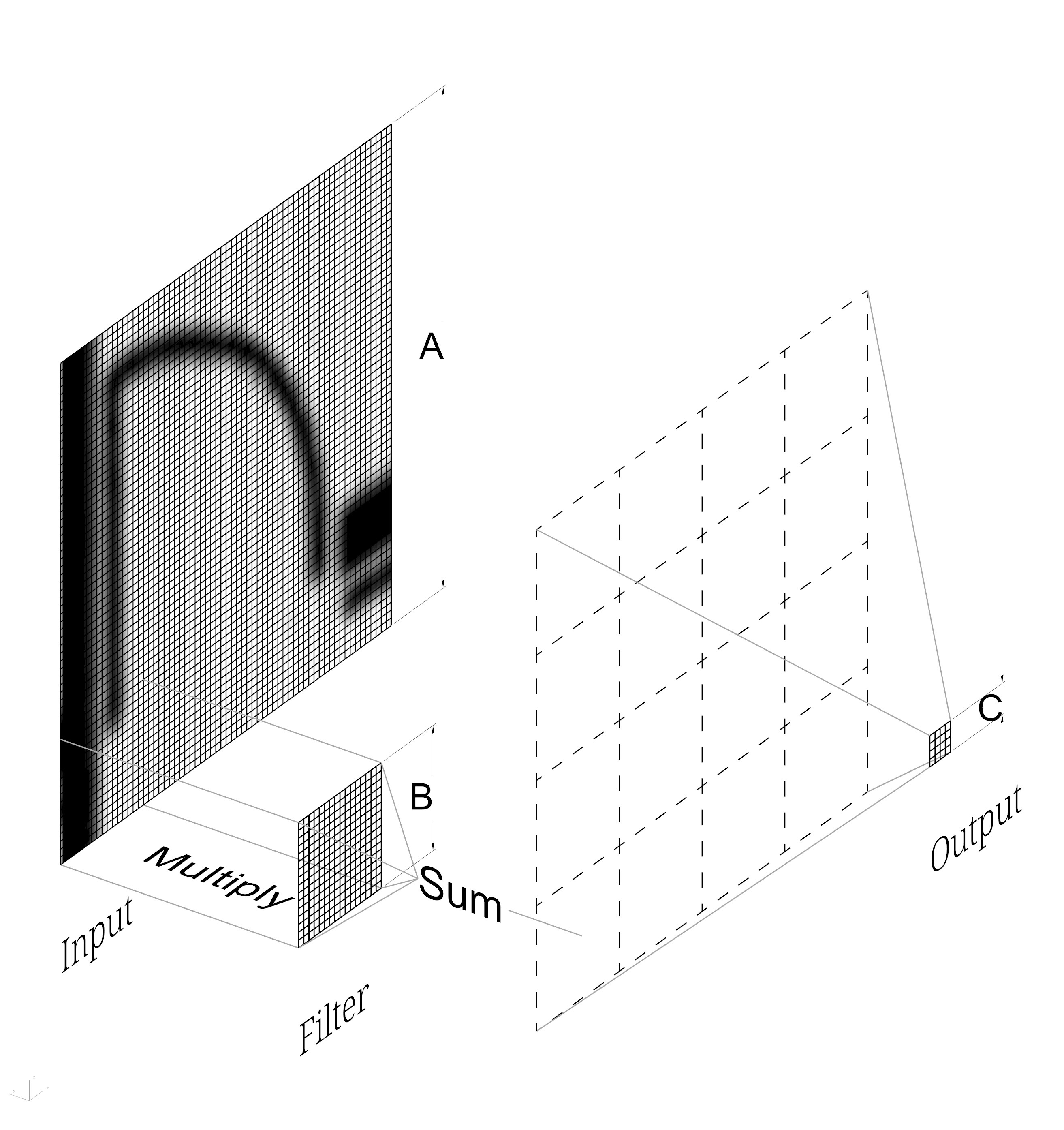

A convolution layer in a convolutional neural network is comprised of filters (also called weights) and optional biases. The convolution operation effectively slides each filter across an input image and multiplies the pixel values in the image element-to-element with the values in the filter. This resulting array of numbers is then added up to produce the final output. How each layer reduces the size of the input is determined by the input dimensions, filter dimensions, stride (the spacing at which the filter is moved across the image), and padding (extraneous pixels added to the input to fit the filter evenly). In the diagram these correspond to:

- Input Dimensions: (64, 64)

- Filter Dimensions: (16, 16)

- Stride: (16, 16)

- Padding: (0, 0)

Because the filter is moved its entire width at each multiplication step, and because its dimensions divide evenly into the dimensions of the input, we get a nice round number for the dimension of our output. In this case A/B=C or 64/16=4. Admittedly, this example is extremely simplistic and a bit contrived. In practice, the filters and strides are typically much smaller, but this makes the diagram extremely convoluted.3 However, in a general way, this is what is happening in all convolutional neural networks.

What is evident in the diagram is that the dimensionality of the data has been reduced significantly in this hypothetical convolution. We have gone from a (64 x 64) image to a (4 x 4) “image.” By stacking these layers in succession, we can steadily reduce the dimensions of the data down to some suitably-sized layer tensor. The nascent ability to stack hundreds or thousands of layers is where the “deep” in “deep learning” comes from.

This depth is enabled by one of the advantages of a neural network: that the layers are composable. The output of the layer in the diagram could be fed into the input of another that reduces the dimensionality further to a (1 x 2) image. This label could then be coded to correspond to a binary door/not door label.

What gives neural networks the ability to express complex ideas like doorness is that each layer can have tens to hundreds of the filters involved in performing this dimensionality reduction. The “learning” of deep learning that happens during training of one of these models is updating the numerical values inside each of the “pixels” in the weight such that the stacks of layers produce values close to the intended labels.

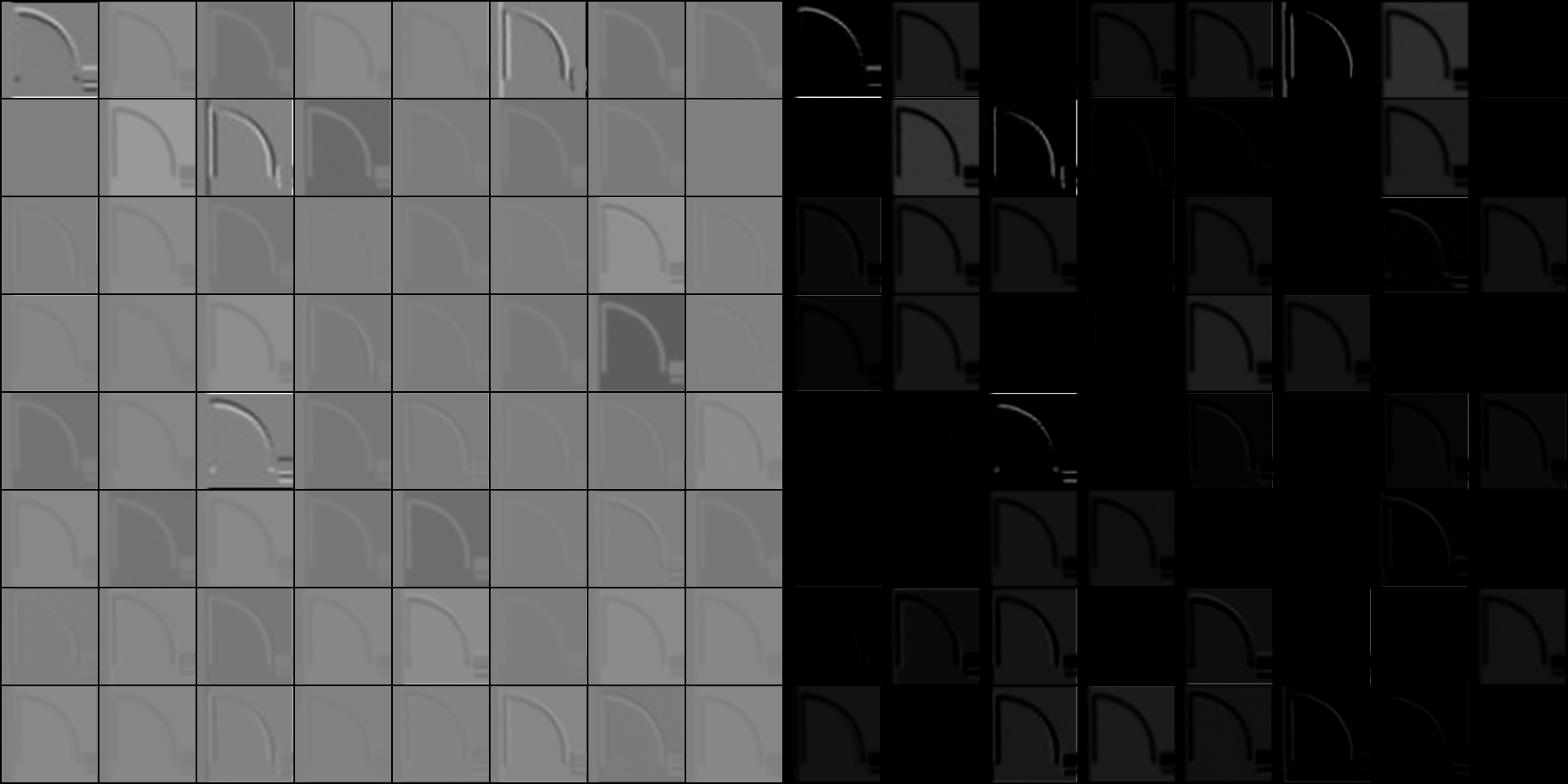

The left half of this image shows the output of the first convolutional layer of an instance of DenseNet that has been trained to convergence (achieving close to one hundred percent accuracy during training) on recognizing doors, windows, rooms, columns, and stairs. The lighter pixels show a strong positive response, while the darker pixels show a strong negative response. The highest responding features appear on the arc and vertical line of the door swing symbol. This indicates that one of the strong doorness-determining features must be this symbol. However, the edges of the walls around the door respond quite strongly as well. So, doorness must be some composite of a gap in a wall and the door swing symbol. Because these concepts can all be encoded as arithmetic combinations of matrices of pixels, there is no need to program them explicitly.

The right half of this image shows the same output after it has passed through an activation function. Activation functions behave like gates on the output of the convolution which allows positive values to pass through without effect while setting all negative responses to zero. This behavior is unique to this particular activation function, a rectified linear unit. This has the effect of only allowing information to pass from the input to the output that will positively affect the final label. When these values are passed to the multiplication step of subsequent convolutions, the zero values will effectively cancel out input from the subsequent filters. This allows the network to retain useful information about many categories in the learned filters (something other than a door, in this case) without that information responding to extraneous input.

It should be noted that although the values of the filter and output matrices are structurally similar and can easily be rendered as images, they aren’t necessarily interpretable as such. The ability to interpret these intermediate states of deep statistical models is an active area of research.4

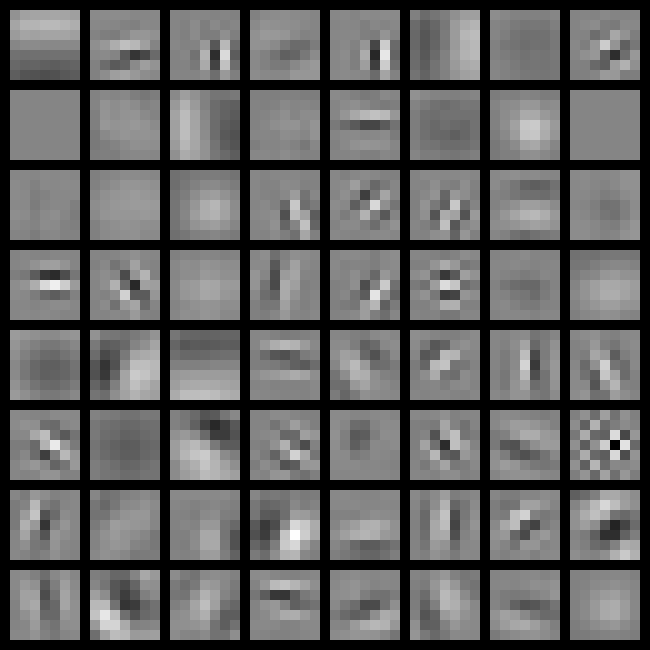

This image of the 64 filters from the same convolutional layer demonstrates how inscrutable the “learned” part of a neural network can be. It is not immediately obvious how any of these filters correspond to parts of the plan drawing of doors. But that is where the representational power of a neural network comes from: not one of these features by itself is coded to mean “door”. Rather, the network has discovered an ensemble of millions of features that all combine to indicate a high probability of the presence of a door.

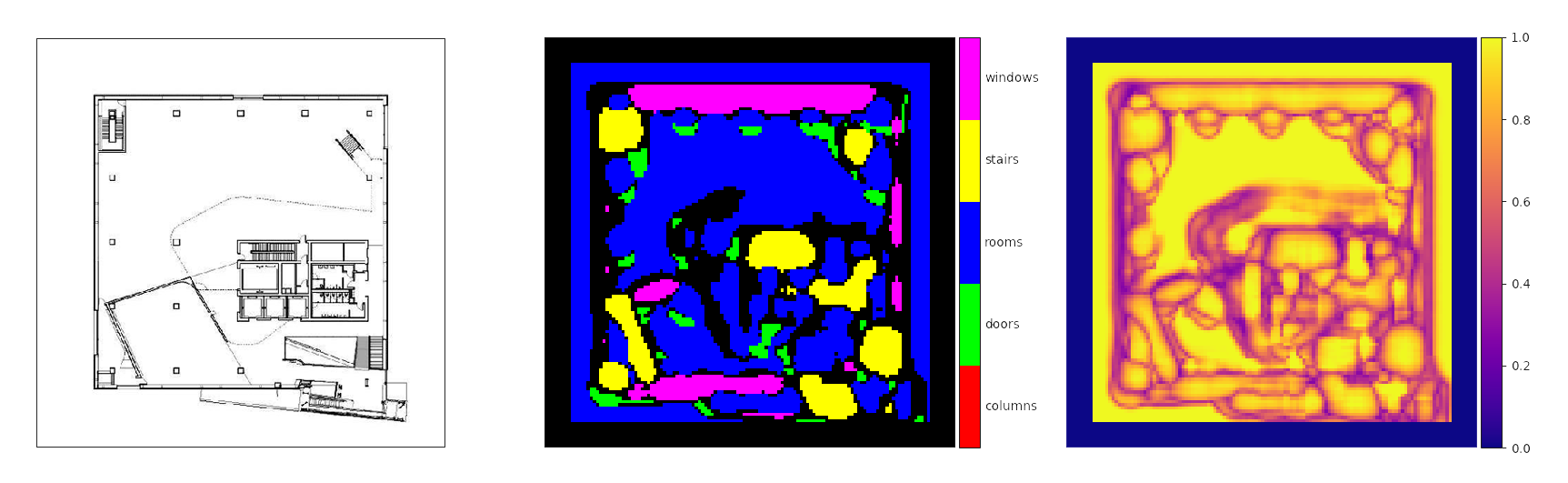

Once we have a classifier that is suitably trained, we can then have it iterate through chunks of an architectural drawing and segment the drawing by where it thinks those classes of objects are. In the example above, the green blob in the lower center of the segmentation shows a correct identification of some doors on the elevator shaft and the central stair, but there are many more false-positive doors distributed throughout the plan.

One of the shortcomings of this approach to the application of a trained classifier is that the network is extremely sensitive to the scale of the drawing. Although the network can achieve greater than 90% accuracy in identifying individual examples, understanding the classes in context is a much more difficult task. The stairs end up having a much higher true-positive rate as they happen to correspond to a proportion of this plan that matches the input size of the trained network. Although machine learning is a powerful tool, it very quickly runs up against domain-specific problems such as these in its applications. However, the flexibility of these numerical methods means that this is a matter of designing a network with an appropriate understanding of image context and is certainly tractable.

From Reading to Writing

Though deep neural networks are capable of categorizing images and of segmenting them by those categories, that is not really design. Fundamentally, design is the generation of new images. Is it possible to do that with the same methods?

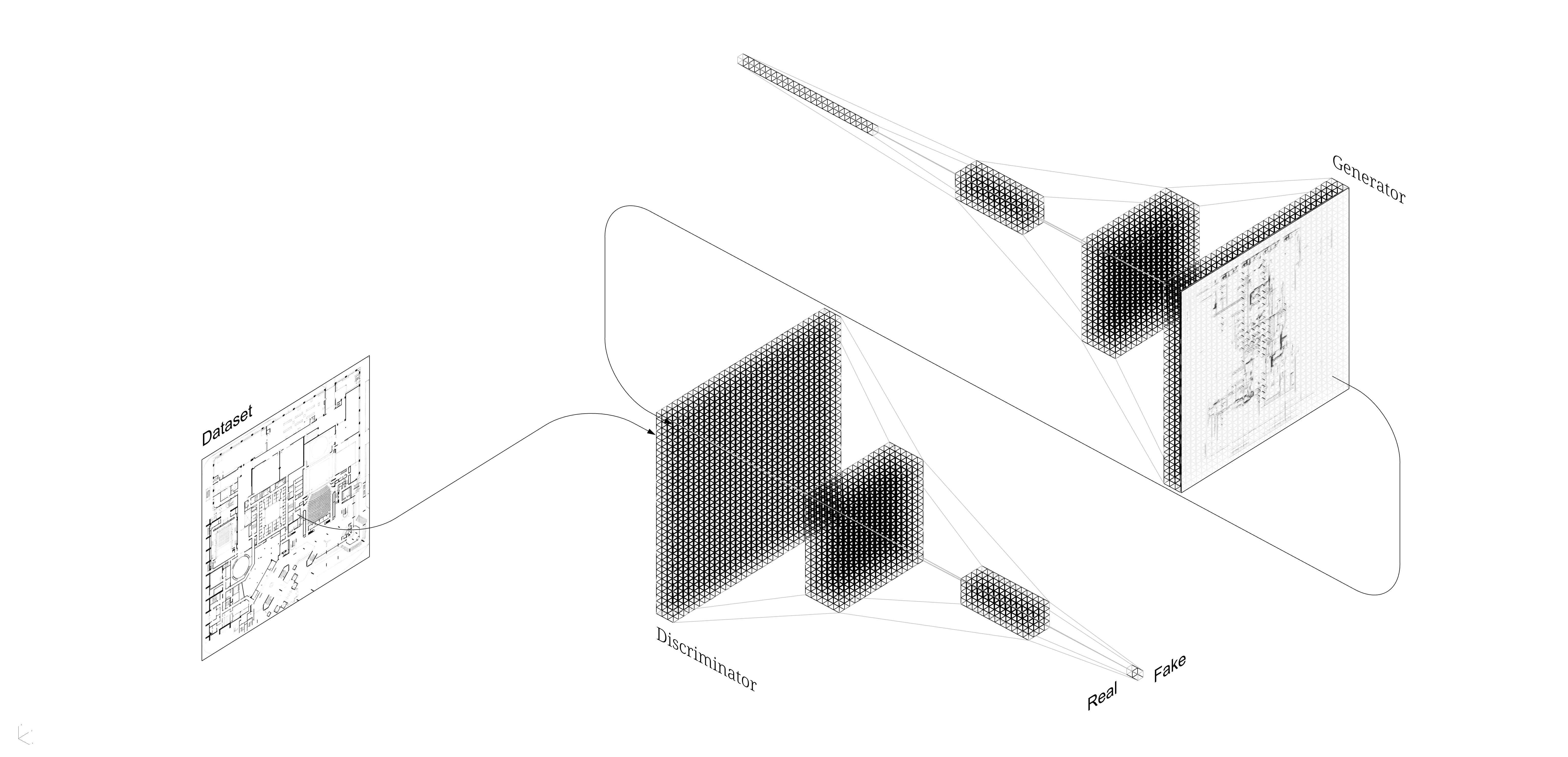

A type of neural network that has been in the news frequently over the past several years is called a Generative Adversarial Network, or GAN. The “generative” part refers to the fact that these networks reverse the shape of a classifier to generate images. “Adversarial” refers to how these models reuse the classifier as an “adversary” to the generator. “Network” refers to (surprise) the neural networkness of them both.

Where a classifier takes a (W x H)-sized image and reduces is to a (1 x N)-sized label tensor, a GAN reverses this — it starts with a random (1 x N)-sized tensor and repeatedly scales it up using a function known as transposed convolution, a kind of spatial inverse of convolution. This generated image is then sent to a classifier similar to the door identifier (here, known as the discriminator) that is trained concurrently to decide if an image is fake or real. The more that a generator fools its discriminator adversary, the higher its score.

As with classifiers, it is possible to apply these models to architectural drawings simply by pointing this network architecture at a dataset of source material.

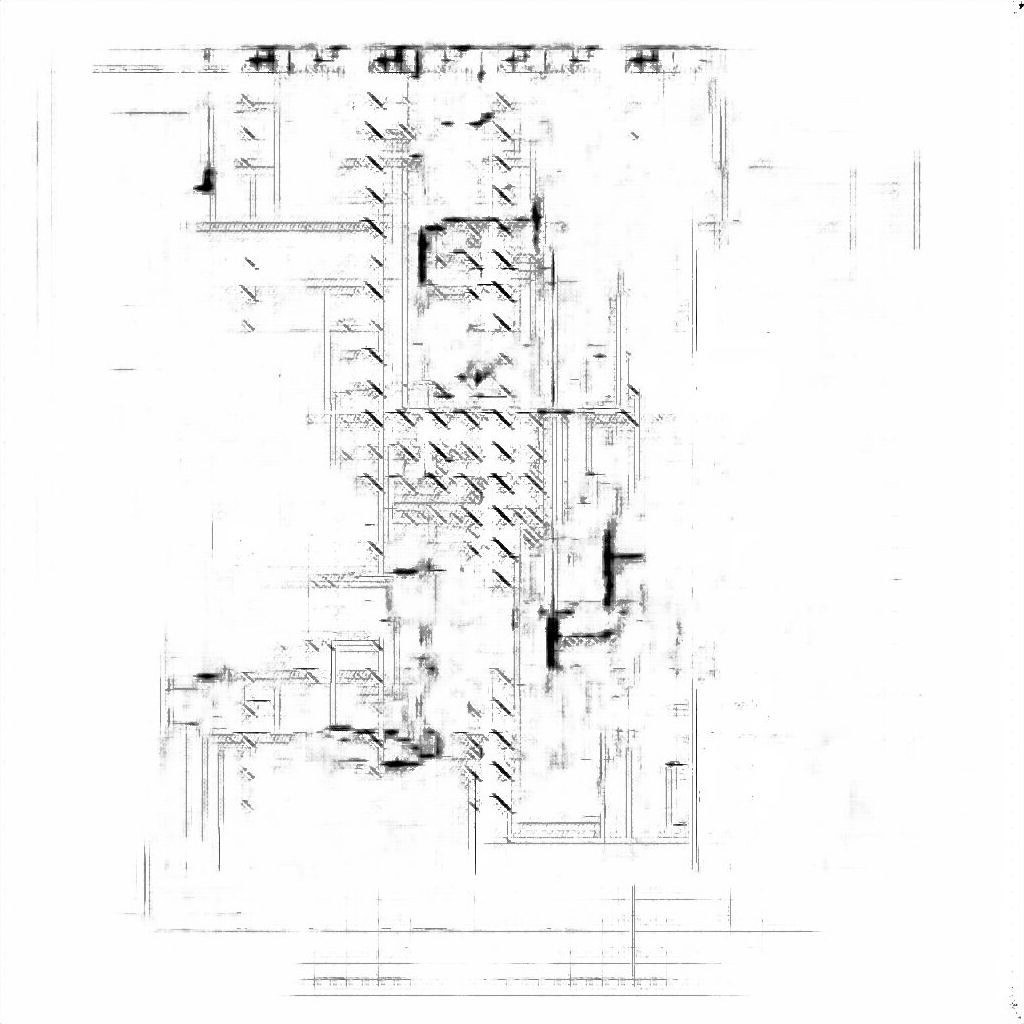

This image was generated with no domain-specific knowledge about buildings, structures, or spaces. Simply by naïve approximation of the statistical distributions of dark and light pixels, it is possible to generate pseudo-architectural drawings. There are clearly deficiencies here, but that is to be expected in the early stages of a technology. What is important to take note of is that it is possible — and in fact, quite easy — to use nascent machine learning techniques to generate the kind of high-dimensional data that architects, engineers, and contractors use to construct the world around us. As our collective knowledge in artificial intelligence and machine learning grows, it will become increasingly vital for design professionals to be able to engage in the design and direction of how this technology is incorporated into the design process.

Neural Space Programs

Even the idea that there is some innately human, affective mental model of “space” is on the verge of obsolescence. Using a method that is not conceptually far removed from generative adversarial networks, DeepMind recently published5 impressive results in generating alternate perspectives of 3D spaces, including top-down, plan-like drawings of simple game worlds6. This suggests that statistical learning has some ability to mimic the translations from perspective, to three-dimensional model, to drawing. In other words, exactly what AEC professionals do every day.

The pressure that statistical machine learning is beginning to apply to design can be healthy and productive for both fields. However, this contingent on the involvement of contemporary design professionals with how these methods are subsumed into future design processes. It has been made evident in other fields that have applied machine learning models, the datasets that are used in training bear the biases of the people that construct them. Professionals from all fields must strive to eliminate this in their work. Designers and engineers cannot abrogate their responsibility to create safe, inclusive, and engaging environments in this future where architecture comes from the machine.

Ultimately, the future is unknown. But, we can look to history to find analogues to guide future decisions. Early generations of design software such as CAD and BIM have become ubiquitous in the AEC industry. These tools were adopted so rapidly that they had more of an effect on the way that we do documentation — not the way that we do design. The inner workings, abilities, and limitations of these tools are still not broadly leveraged by the professionals that use them.

Tesla’s Director of Artificial Intelligence, Andrej Karpathy, has referred to machine learning-based applications as “Software 2.0”7. This refers both to their different programming paradigm, which happens by learning rather than explicitly programming functions, and to their incorporation into our existing software platforms. By relating the work of AEC practitioners to machine learning techniques and terminology, we hope to provide a route between these two domains so that designers and engineers can take an active role in the development of Design Software 2.0.

-

Harvard Business Review and Autoesk, Inc. The Next Wave of Intelligent Design Automation. 2018. ↩

-

Huang, Gao et al. Densely Connected Convolution Networks. 2016. ↩

-

Excellent examples of animated diagrams can be found here. ↩

-

Eslami, Ali S. M. et al. Neural Scene Representation and Rendering. 2018. ↩